Improving Diagnostic Equity In Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening

- Terry Wright’s law will require that all known CF-causing gene variants be used for newborn screening, carrier testing and diagnostic testing for CF.

- The law also requires that reports of newborn screening test results that go to primary care and other providers specifically mention that a normal newborn screening test does not eliminate the chances of any screened disorder.

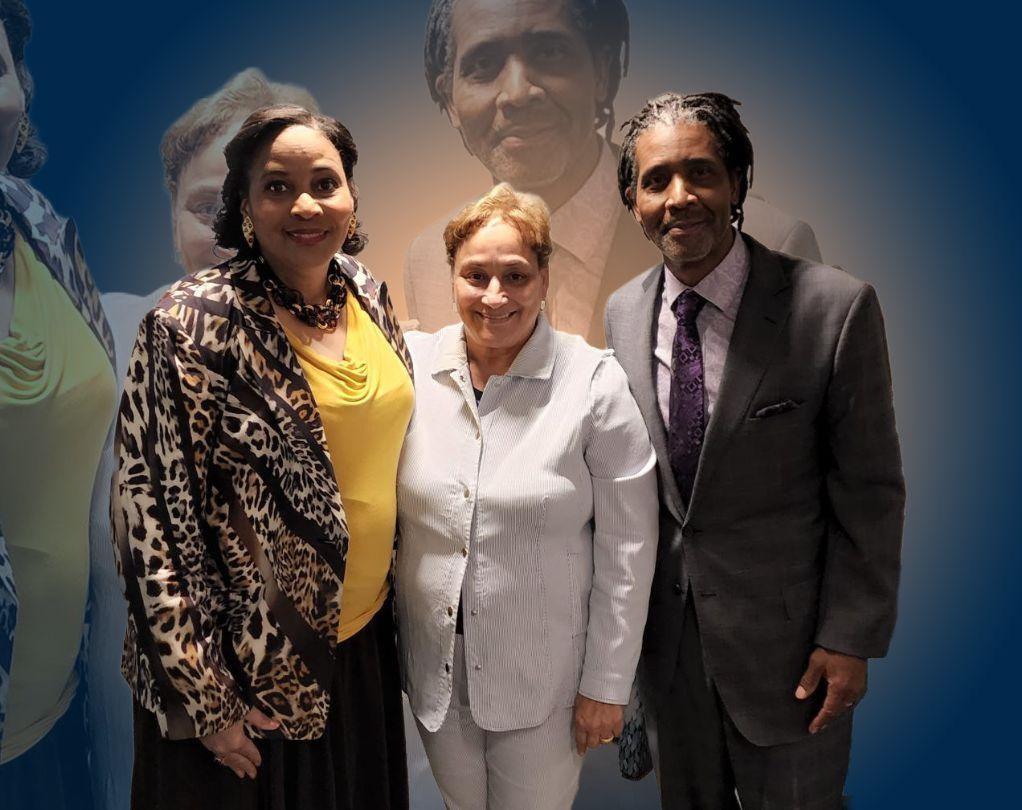

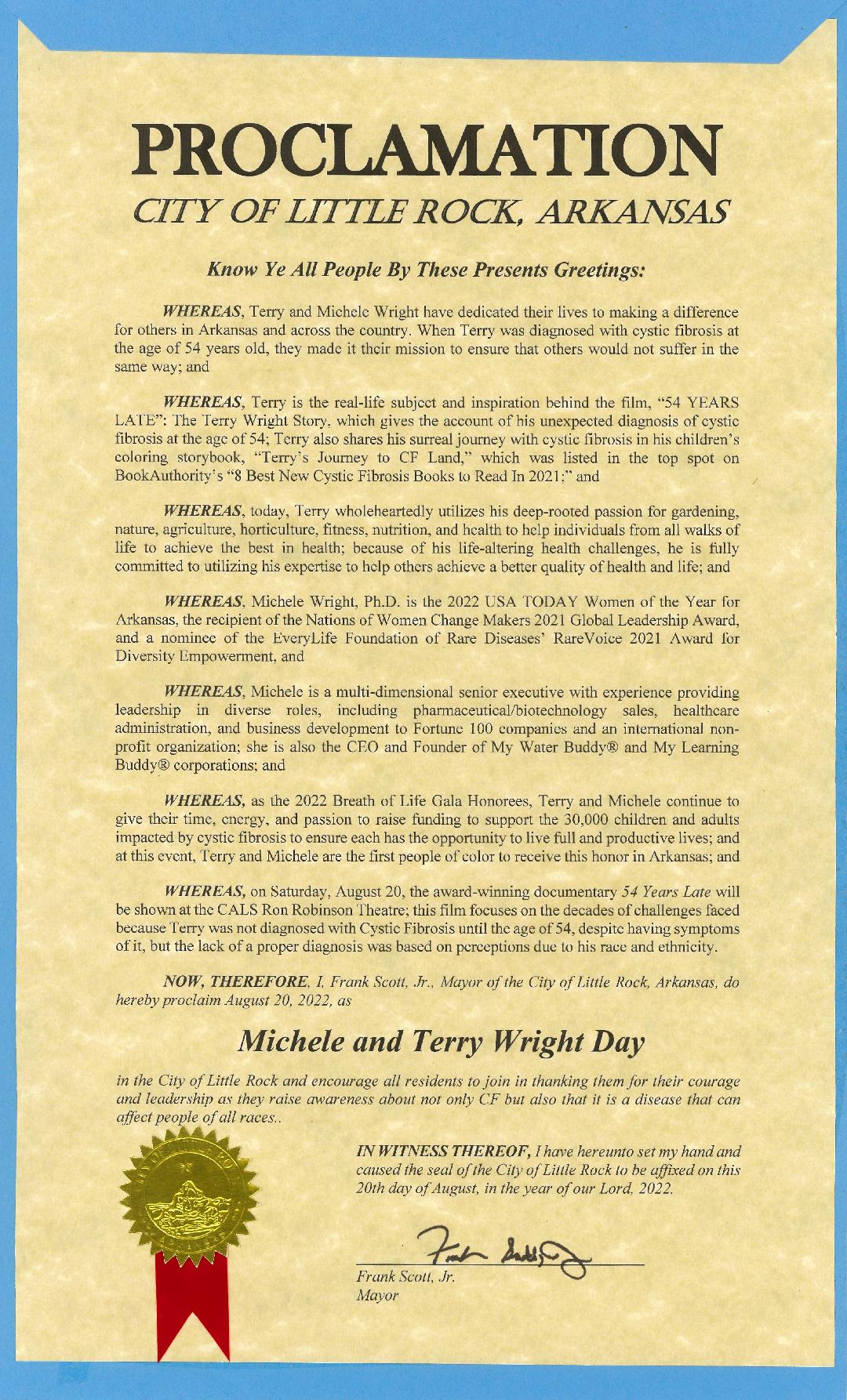

The National Organization of African Americans with Cystic Fibrosis (NOAACF) was cofounded by Michele Wright, Ph.D. and Terry Wright with a mission to engage, educate, and raise CF awareness in the African American community to help bring valuable resources, knowledge, empowerment, and support to CF patients, families, healthcare professionals, and the community. Through widespread involvement, partnerships, advocacy, and outreach, NOAACF’s program scope is to ensure that the Cystic Fibrosis diverse community is educated, informed, and made aware of CF’s existence, prevalence, and impact on underrepresented communities.

Terry Wright, a 62-year-old African American man with Cystic Fibrosis (CF), was not diagnosed until the age of 54, although he had been hospitalized and seen by an array of healthcare practitioners throughout his life with typical CF symptoms. Because newborn screening was fully implemented throughout the United States in 2010, you may think that Terry could have been spared the many years of suffering leading up to his diagnosis. However, it is very likely that current newborn screening strategies would have missed Terry’s diagnosis too.

Newborn screening for CF is implemented by each state individually. In most states, a limited panel of variants in the CF gene that causes CF are tested. The most common is always included: the F508del mutation, one of >2000 variants in the CFTR gene pool seen in nearly 90% of White, non-Hispanic people with CF. But many studies have confirmed that F508del is much less common in people who are Black, Asian, Native American /Indigenous population with CF, and/or Hispanic, sometimes called Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) or racial and ethnic minority groups. Furthermore, BIPOC individuals are more likely to have rare CFTR mutations that are also not included in most state CFTR variant panels.

Lack of genetic equity in newborn screening panels leads to not only health inequality and health disparities, but late diagnosis in underrepresented individuals such as the devastating case with Terry Wright. Because Terry has two rare CF-causing gene variants (sometimes called mutations), 1853T>2C and 2738A>G, his case would likely have been missed if newborn screening was being performed when he was born. Lack of detection of CFTR variants causing CF is an issue for all minoritized or BIPOC populations in the United States. Race is a sociopolitical construct that should not be confused with ancestry. Nevertheless, different CF gene variants are distributed differently across the world, and it is clear that newborn screening, carrier screening, and limited diagnostic panels are less likely to detect CF-causing gene variants in minoritized populations.

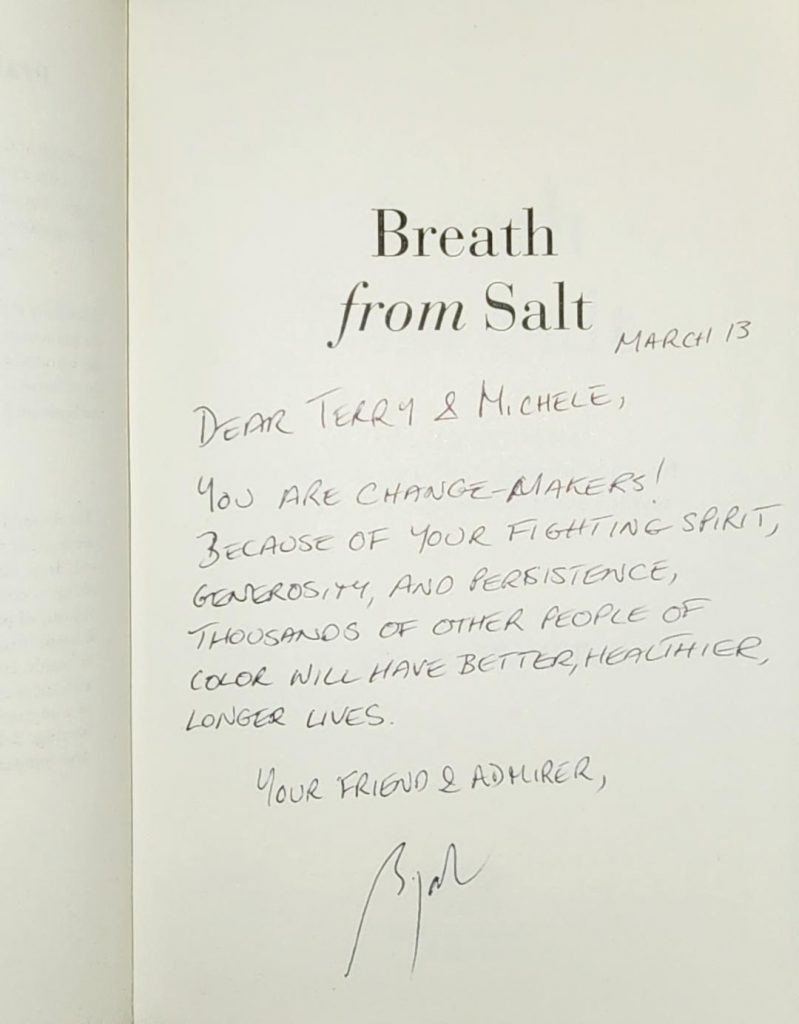

Therefore, NOAACF is advocating for Terry Wright’s Law to improve equity in CF newborn screening. Terry Wright’s law will require that all known CF-causing gene variants be used for newborn screening, carrier testing, and diagnostic testing for CF. This will markedly improve equity in newborn screening for BIPOC individuals, while also benefiting all people with CF who may have delayed or missed diagnosis due to the presence of rare CFTR variants. This is technically possible today with available testing. Because some CFTR variants remain uncharacterized and because other sequence changes, such as deletions, can cause CF, the law also requires that reports of newborn screening test results that go to primary care and other doctors specifically mention that a normal newborn screening test does not eliminate the chances of any screened disorders. The road ahead requires approval of new technology by regulatory agencies, legislative action, and resources for implementation across the country. Nevertheless, it is feasible and we will continue our efforts until any baby born anywhere in the US has an optimal and equal chance of having their CF detected by newborn screening.